AFP photograph by Victor Drakov

In 1986, 115,000 people were forced to leave “for 3 days and no more” starting 36 hours after the Chernobyl explosion including the inhabitants of 81 villages. After 1986, another 200 000 people from Belarus, the Russian Federation and Ukraine were relocated. If you really wish to visit this period again this website will bring you almost up-to-date. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/chernobyl-accident .

Some of the residents started to return to their villages within weeks. These waves continued for about 4 years despite efforts to stop them. “Samosely” or selfsettlers are still residents of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone – mostly Babushkas. By 1987, 1200 people had returned to live in their old homes. Eventually women past child-bearing years were allowed to stay. That means that nearly 40 years later the surviving residents have to be at least 90.

Today, there are about a 100 still surviving. This number has dropped from about 250 only a few years ago. They live off the land, growing their own food and picking Cesium 137 laced mushrooms. They have foraging pigs and chickens.

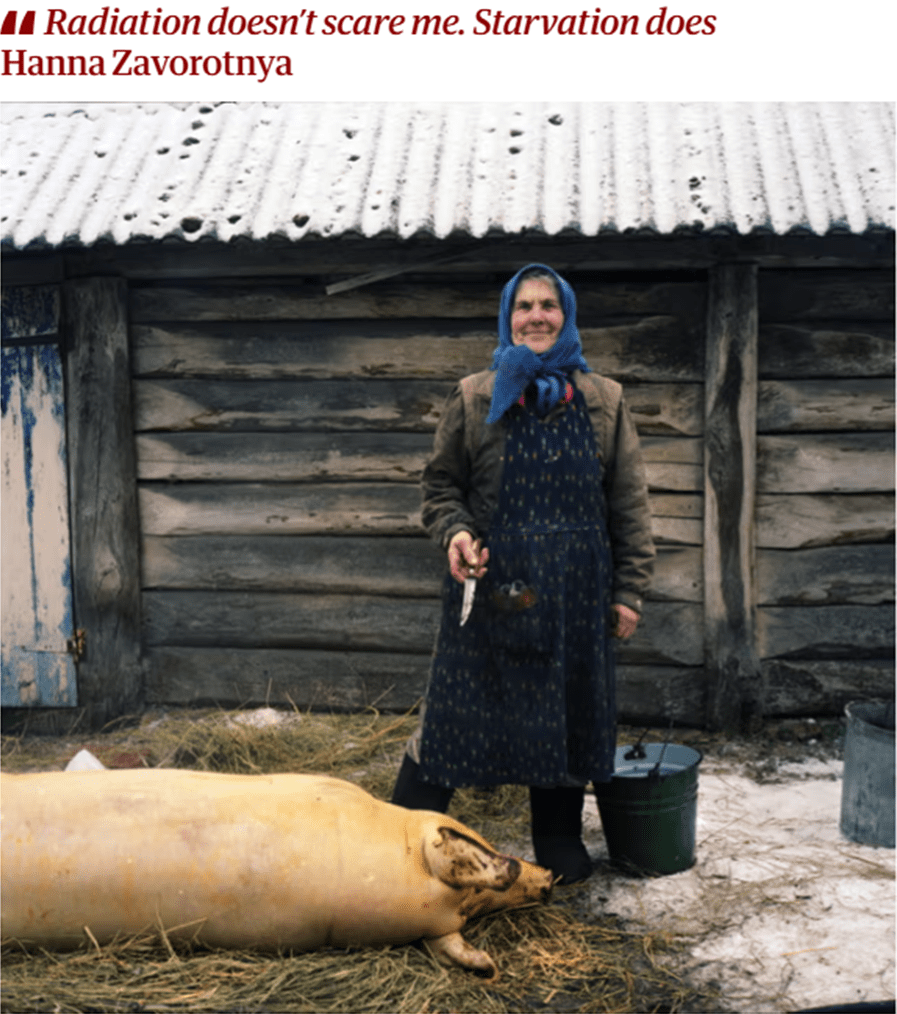

Hanna Zavorotnya and a pig in front of her home in the CEZ. Photo: Rena Effendi

Hanna is one of the 3 stars in the 2015 documentary “The Babushkas of Chernobyl“. It can still be viewed or bought on the web from various sources.

The Samosely have lived hard lives and remember so much: the starvation of 1932 under Stalin when millions died, the brutality of Nazi occupation then forced eviction from their Motherland. Now they fight to keep their crops from wild animals. Finally, the Russians took over the area again for a time following years of Ukrainian independence. The war continues. For a time, landmines were in parts of the forests.

The Joy of Harvest: Photograph by Yuli Solsken

Photo by Jorick de Kruif in 2018: Ivan Semenyuk was 82 years old and lived in the house he built in the 1950s in the village of Paryshev.

When interviewed in 2018, Ivan was growing cabbages, tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots, shallots, potatoes and beans on his allotment. He loved to fish and gathered mushrooms, berries and medicinal herbs in the forest. A mobile shop, which was supposed to visit every Friday, brought food, household chemicals and basic necessities, which he could buy with his pension which is delivered to him and other elderly inhabitants of the zone. Ivan has mains electricity, and recalls that they did not have to pay for it for two years after he returned.

He draws water from his own well on his land. He has a mobile phone, television and radio, and keeps in touch with the outside world between visits from his son.

Like other inhabitants Ivan had trouble with wild animals destroying

vegetables growing in his garden. He respected radiation but greatly feared the packs of wolves and the snakes. He and his dogs had been attacked by large packs of wolves, 6 dogs being killed in one week. Eventually, the authorities permitted him to shoot wolves.

What of the radiation? Ivan explained how men with dosimeters checked levels in his well and land. He stated that there was now no radiation in the village. (Visitors are warned not to eat anything in the zone.)

There is no doubt that like the animals of the CEZ, the Samosely experienced higher levels of ionising radiation than the normally accepted levels for humans. However, I suspect that the levels were in the low dose range. Yet these people seem to have outlived those of similar age and background who left their “MotherLand” and lived elsewhere. I would like to have seen better radiological data.

Next time: thousands still work at the nuclear power stations. A few people live in the ancient city of Chernobyl.