Cyclone Alfred was a 1 in 50y event that brought low grade cyclonic winds to southeast Queensland and northern NSW over a period of a week between March 4-11. However, it was the rain and associated flooding after the cyclone crossed the coast that caused the most widespread damage. The multi-day duration of cloud cover that the system brought is the basis of this blog.

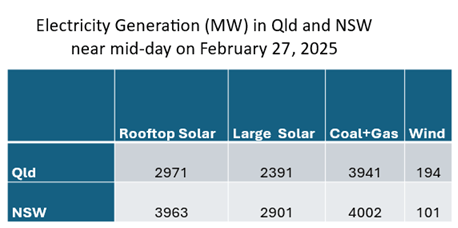

Rooftop solar refers to solar panel on roofs, and this is dominated by residential (domestic) installations.

Currently more than 1-in-3 Queensland homes have rooftop solar, the highest rate of any Australian state or territory, with 6 GW having been installed by early 2024. Three quarters of the population of Queensland lives in the southeast corner of the state. Thus, three quarters of the dwellings with rooftop solar are located in this geographic region and account for the great majority of rooftop solar being fed into the grid during the day.

The table below shows the contributions of small (rooftop) and large scale (solar farms) inputs in MW to the Queensland grid in the middle of a typical bright sunny day. The electricity coming from coal and gas, and from wind are included for reference.

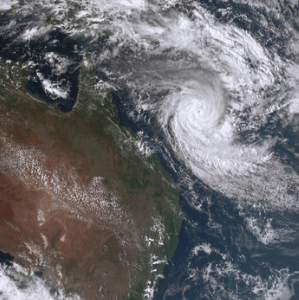

These figures were taken from the NemWatch site on February 27 when the cyclone and associated cloud was well off the coast (satellite image below) and the east coast was largely cloud free. I have also included the comparable figures from NSW for reasons that will soon become apparent.

For both states, solar was making by far the largest contribution to electricity generation.

Satellite Image (source: BOM) on February 27 showing cyclone Alfred and associated cloud well off the east coast.

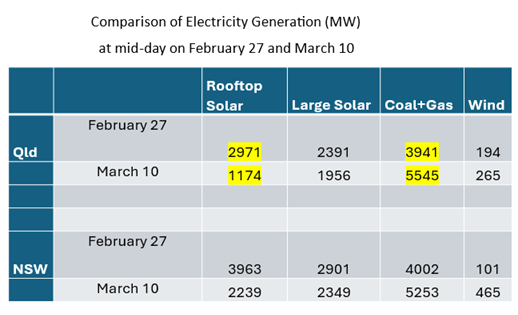

The table below compares the data from February 27 with that at a similar time during the day on March 10 when there was extensive cloud cover over southeastern Qld and northern to central coastal NSW (see satellite image below).

What is immediately apparent from this table is the huge 60% drop (1800MW) in rooftop solar output seen on March 10. There is also an almost 20% drop in the output of large solar, but this is small in comparison. The 2200 MW loss from solar had to be made up by coal and gas generators.

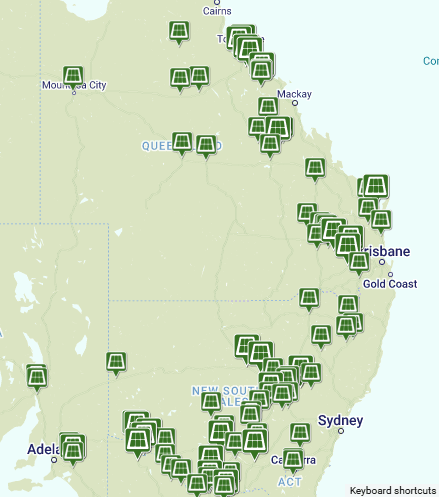

The question is why rooftop solar was impacted so much whereas large solar only suffered a modest decline. The reason is location! The locations of large-scale solar plants down the east coast of Australia are mapped below. What is immediately apparent is that in Queensland most of these are located further inland and north of the cloud covered area.

In New South Wales there was 45% drop in rooftop solar, and a similar 20% drop in large solar. Once again for similar reasons to Queensland where the cloud cover extended down the coast to the Sydney area which hosts the majority of rooftop solar in New South Wales. However, the drop wasn’t as big in Sydney because there was less cloud cover.

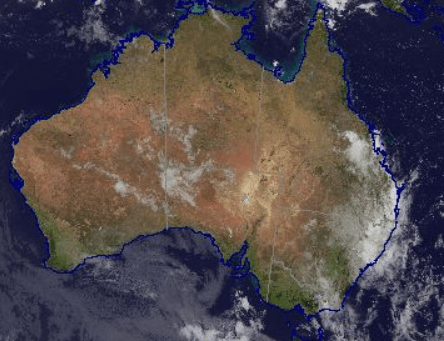

Satellite Image (source: BOM) on March 10 showing extent of cloud cover in southeastern Queensland and northern New South Wales.

Locations of large solar farms in Qld and NSW https://reneweconomy.com.au/large-scale-solar-farm-map-of-australia/

This rooftop solar drought lasted for several days after Alfred, with coal and gas power continuing to make up the shortfall. Given that there is very little storage for the renewables component of the grid, this highlights the vulnerability of having the bulk of the rooftop solar generating capacity in the one geographic area. Even for those fortunate enough to have battery storage for their rooftop solar, this backup would not have been sufficient to last for the days of cloud cover.

This situation occurred again in March when a broad band of cloud blanketed much of southeastern Queensland for much of the month, extending across eastern New South Wales in the last week of March (satellite image for March 28 below). The solar output figures for Queensland and New South Wales at mid-day on March 28 are compared with the “reference” February 27 outputs below. The almost complete “collapse” of large-scale solar outputs in both Queensland and New South Wales was caused by the cloud extending much further inland in both states, and further north in Queensland than was the case on March 10. In both states, but particularly in NSW, the loss of solar was partly offset by an increase in wind generation.

What this shows is that the concentration of rooftop solar in the large coastal cities of Brisbane and Sydney exposes the vulnerability of the state’s solar generating capacity to cloud cover, especially during the summer season. This situation is likely to be worse in the coming years when it is likely that there will be increased southerly excursions of warm moist air from the tropics. These periods can last for days at a time and highlight the critical need for much more medium and long duration storage to firm even the current penetration of renewable generation.