I began my last blog by noting that sufficient storage, especially medium to long term storage will be critical to ensuring reliability for a renewable dominated grid. Here I will be discussing battery storage from home to utility scale, and the critical role that pumped hydro must play for long duration storage.

Batteries

The big benefit of batteries is their flexibility. Energy stored in batteries can be discharged quickly when needed. However, individual battery systems of the Lithium-ion (Li-ion) type can only currently provide about 2-4h of backup supply at full discharge rate. Below I discuss separately battery use for rooftop and large scale solar and wind.

Rooftop (Small) Solar

At the end of 2024 there were almost 4 million rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) installations in Australia on 1 in 3 homes, totalling about 25 GW of nameplate capacity. This sounds like a lot and indeed in the middle of the day this is the biggest single source (up to 40%) of the electricity entering the grid in Qld, NSW and Vic. Installations are increasing by about 350,000 annually However, this situation is starting to lead to serious problems with maintaining 24/7 stability of the grid, largely because only 1/14 of the millions of rooftop solar installations have any associated storage! One of the major reasons for this situation has been the high cost of batteries which has made them economically unattractive for most homes.

It is absurd situation that power prices have often reached negative values during the middle of the day as a result of lack of system storage, this power is being wasted or spilled. A quotation attributed to the founder of Solar Quotes appeared in recent ABC news item: (https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-03-16/australian-solar-feed-in-tariffs-have-plunged-99-per-cent/104986534 )

“But when your power is coming from the sun, there’s no fuel. We’re not short of sun. It’s not really wasting it.

“Worrying about wasting surplus solar energy is kind of like worrying about the rain coming out of the sky when your rain tanks are full.”

I contend that this is a perverse statement. The reason being that while the energy from the sun might be free, the solar panels that convert the light to electrical energy require a lot of energy (mainly from coal) and material inputs to manufacture them. So, spillage effectively amounts to a decrease in the emission savings that can be attributed to solar. And no one is taking that into account!

There are proposals to install larger scale community batteries to take some of the daytime solar surplus, but the issue of who will pay for these initiatives beyond a few government-subsidised trial locations remains to be seen. Likewise daytime charging of electric vehicles may ultimately take up some of the rooftop solar surplus, but that is contingent on many more EVs entering service and charging stations being installed.

There is also the (policy) expectation that the batteries in EVs will be able to act as storage systems for the home (an EV battery is often 4-5 times bigger than a typical 12-14kWh home storage battery), and that this will ultimately make up a substantial proportion of short-term storage for the grid. However, as of the end of 2024 South Australia was the only state that allows bidirectional chargers to be installed in homes. Bidirectional chargers are also expensive, costing around $10,000, and the payback time for households is still more than ten years. https://www.mynrma.com.au/open-road/advice-and-how-to/what-is-v2l-v2h-v2g

Utility (Large) Batteries

There is currently about 18GW of large solar PV and 11 GW of wind power in Australia. However, very few of these projects currently have significant co-located storage.

Li-ion

The so-called “big” batteries are being installed to store surplus power from the renewables. About 8GW of largely Li-ion storage, typically with a duration of 2-4 hours, is currently under construction and being commissioned.

To meet projected grid storage requirements there will need to be 7 GW of battery type storage installed every year.

Decommissioned coal-fired power plant sites have been preferred locations for large-scale battery projects due to their existing electricity transmission infrastructure and previous industrial usage. AGL is building the 500MW/ 1GWh Liddell Battery Project in New South Wales. In May 2024 Queensland announced it was doubling the size of its Stanwell Clean Energy Hub battery, to 300 MW/1200 MWh. A battery at Collie in Western Australia will have a 219 MW/877 MWh first stage, with potentially up to 1000 MW/4000 MWh. To put these examples of current projects into context the initial “big” battery in South Australia had a capacity of only 130 MWh.

However, even the biggest of these batteries, is “small” compared to what will be needed. Not only that but typically they can only provide 2-4h storage. So, a 500MW battery might sound large but typically it can only provide full power for 2-4h (ie 1000-2000 MWh). We are going to need a lot more of these batteries if the 2030 renewables target is to be met.

One advantage that batteries have over pumped hydro is that they can be installed relatively quickly.

Like solar panels, the operational lifespan of current Li-ion batteries is relatively short, needing to be replaced around every 15 years. This presents a challenge for Australia’s net zero ambitions, as batteries that have been installed through the 2020s are likely to be need to be replaced in the 2040s – when the transition to net zero by 2050 will be imminent.

One critical aspect of Li-ion batteries that is rarely mentioned when the capacity of utility batteries is stated is that unless they are operated routinely between 20-80% of capacity then their life can be substantially shortened. This will constrain the effective supply capacity of a battery system if lifetime is to be maximised.

Flow Batteries

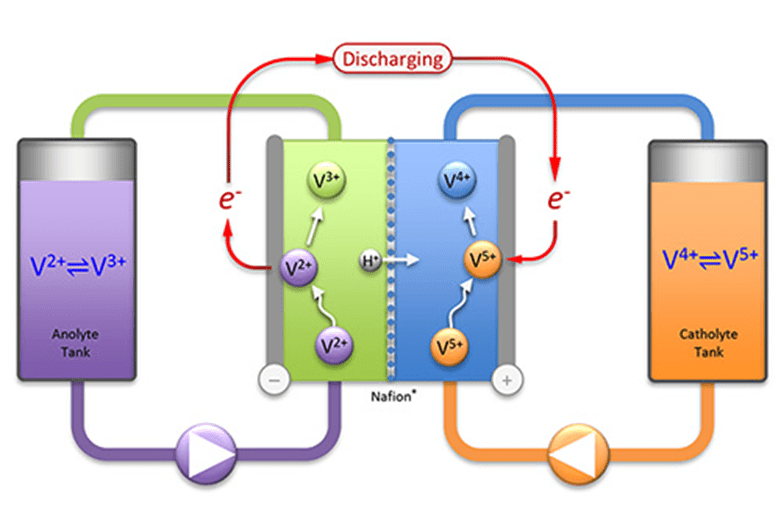

The other type of utility scale battery that is starting to emerge are flow batteries. These function a bit like pumped hydro because they work on the principle of the electrolyte fluid being circulated from charge to discharge tanks. Unlike Li batteries they can be made very large, and can be easily scaled up by increasing the capacity of the electrolyte storage tanks. They also have potentially a very long life, they cannot catch on fire, and the components are easy to recycle. They are ideal for large stationary utility storage. Vanadium flow battery technology was originally developed at the University of NSW in 1980s.

This is a schematic of a Vanadium flow battery, showing the different charged states of the Vanadium.

The largest commercial vanadium flow battery project is currently in China with a capacity of 175 MW/700 MWh. Australia has the third largest vanadium resource in the world so is potentially ideally placed to capitalise on this technology for future storage requirements. A potential 100MW/400GWh battery project is currently undergoing commercial evaluation in Perth. (https://www.ess-news.com/2024/11/06/australian-made-vanadium-flow-battery-project-could-offer-storage-cost-of-166-mwh/)

Pumped Hydro

The key difference between a pumped hydro scheme and a traditional hydropower operation is that pumped hydro is not a net generator of electricity. It is both a load and a generator, at different times, as needed. There are over 120 operating hydroelectric power stations in Australia, large and small, mostly located in south eastern Australia. In contrast, there are currently only 3 operating pumped hydro systems.

Source: https://www.energy.gov/eere/water/pumped-storage-hydropower

Pumped hydro systems currently account for an astounding 95% of electricity generation storage globally. This is not surprising given the scale of such systems (multi-gigawatt) and the high (70-80%) round trip efficiency (RTE) of a pumped hydro system. (https://decarbonization.visualcapitalist.com/all-commercially-available-long-duration-energy-storage-technologies-in-one-chart/).

RTE measures the effectiveness of a storage system by measuring the ratio of energy output to energy input during a full charge-discharge cycle. The higher the RTE, the lower the losses and therefore higher the efficiency. Even more compelling is that the return on energy invested compared with return over its lifetime (EROI) for pumped hydro is almost 30 times higher than Li ion batteries! Pumped hydro projects also use very well-known and tested technologies and infrastructure that can last 50 to 100 years or even longer, compared to the much shorter (15-20 years) lifespan of batteries.

There is another compelling attraction for pumped hydro. Hydropower systems are synchronous generators. That is, they are similar to coal and gas fired thermal power stations running large turbines and do not require the elaborate stabilisation and conditioning (with associated costs) needed for direct inputs from solar and wind.

However, there is a major problem with pumped hydro compared with large battery systems that can be installed in months following delivery of the components. Pumped hydro systems are big infrastructure projects with long timelines required for environmental approvals, site characterisation, and construction.

So, what pumped hydro capacity does Australia currently have? The fact is that there has been very little hydro development in Australia since the 1970s. The plot below shows the annual output of hydro schemes in Australia from 1970 to 2021. In essence it has flatlined since 1970.

Data Source: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Australian Energy Statistics, Table I, September 2022

There is currently only 1.4 GW of operational pumped hydro capacity in Australia, with none having been commissioned since Wivenhoe in 1984. A further nominal 2GW is currently under construction as part of the much delayed and cost escalating Snowy Hydro 2 scheme.

Pumped Hydro (existing and under construction) in Australia

| Scheme | Status | State | Capacity MW | Duration h |

| Tumut 3 | Operating | NSW | 650 | 20+? |

| Wivenhoe | Operating since 1984 | Qld | 500 | 10 |

| Shoalhaven | Operating since 1977 | NSW | 240 | ? |

| Snowy 2 | By 2029? | NSW/Vic | 2000 | 170 |

| Kidston | By mid-2025? | Qld | 300 | 7 |

| Borumba | By 2030? | Qld | 2000 | 24 |

https://pumpedhydro.com.au/education/pumped-storage-hydropower-in-australia/

To get a sense of scale for the numbers that are in the Table the National Energy Market currently supplies about 25000 MW of energy for each hour of the day. Whist the duration of the Snowy scheme is listed here as 170h there has been serious debate over whether this is realistic given system operating constraints. Indeed, it may only be half this in practice. (https://theconversation.com/snowy-2-0-will-not-produce-nearly-as-much-electricity-as-claimed-we-must-hit-the-pause-button-125017).

However, there is absolutely no doubt about the cost effectiveness of the Snowy project, even at the current estimated cost of $12Bn. For comparison, it would cost hundreds of billions of dollars using Li-Ion batteries to provide the equivalent amount of long duration storage.

Until the end of 2024 the 5GW Pioneer Burdekin pumped hydro scheme was being proposed for Qld. This would have been the largest pumped hydro scheme in the world, at an estimated cost of $20-30Bn. However, this project was terminated following the Qld State election and change of government, in favour of a number of smaller schemes, including the 2GW Borumba project. However, even the Borumba project may be scaled back to 1.5GW. Each of these pumped hydro schemes will require years to fully plan, obtain environmental approvals, and construct. There are other pumped hydro projects that are being considered but they are too early in the planning and approvals process to be mentioned here. https://www.allens.com.au/insights-news/insights/2025/02/pumped-hydro-current-projects-in-development-across-australia/

It is clear that there is no way that sufficient long duration storage is going to be in place by 2030-2035 when the current national policy settings require the 80% renewable electricity target to be met, as major coal-fired generators are scheduled to be phased out.

In my next instalment I will discuss what Cyclone Alfred has taught us about the vulnerability of electricity supply from rooftop solar in Queensland during adverse climate events in the southeast of the state.