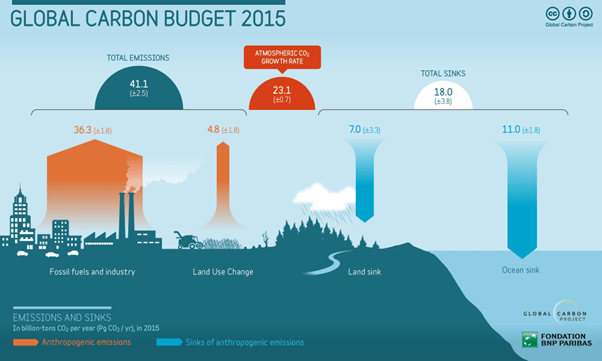

Currently, our land with its forests and other vegetation removes a massive 30% of our carbon emissions every year. Unless natural carbon removal processes are maintained, we have no chance of ever restoring carbon dioxide levels in our atmosphere to tolerable levels.

The classic diagram below is misleading in that it is too simple. The “young growing forest” in the third panel is shown as sequestering more CO2 than the “standing forest” or natural forest. This is initially true but depending on its origin and future, the young growing forests can end up as a net carbon sources or at best carbon neutral.

There are two main groups of “young growing forests”: plantations and regrowth forest. If regrowth forest survives long enough and is ecologically diverse enough, it can take on the characteristics of older forests when it reaches an equilibrium between death and decay and natural tree replacement.

Old-Growth Forests Store Carbon Differently

When it comes to fighting climate change with forests, it’s easy to think all trees are equal. This thinking has led to simple approaches that focus on tree numbers rather than the complexity of the forest. However, science tells a different story: old-growth forests and tree plantations store carbon in distinct ways, and this matters significantly for climate action.

https://www.ecomatcher.com/why-old-growth-forests-store-carbon-differently/

Old-growth forests are sophisticated carbon storage systems that have been built over hundreds or even thousands of years. There are trees of different ages, sizes, and species, creating a complex living structure. This diversity is crucial for storing carbon. Trees do die but they are replaced, and the system reaches a wonderful equilibrium which continually sequestered carbon. The massive tree trunks in old-growth forests represent centuries of carbon buildup. A single large tree can capture as much carbon in one year as an entire medium-sized tree contains in its whole body. In some forests, large trees make up just 6% of all trees but account for 33% of the forest’s yearly growth. This shows why size matters when it comes to carbon storage.

Most importantly, old-growth forests continue to store carbon in many different ways and places. Above ground, carbon is locked in living trees, dead standing trees, and fallen logs that take decades to break down. Below ground, massive root systems and centuries of built-up soil create huge underground carbon vaults. This multi-layered storage system provides both capacity and strength.

Many of Australia’s native forests are younger remnant forests but these forests are also living ecosystems and actually work nearly as hard for us, not just by sequestering carbon and preserving our biodiversity but by helping to cool our land through evapotranspiration and shading and forming a critical part of the water cycle. Forests can store a lot of water, helping to mitigate floods, seed clouds and clean water.

Do Plantations Mitigate Climate Change?

Plantations are typically planted with a single species all at the same time. Plantation forests can remove between 4.5 and 40.7 tons of CO2 per hectare per year during their first 20 years of growth. However, they all reach maturity together and die together, throwing all that carbon back into the atmosphere if they are not logged first. Depending on the use of those forestry products a little of the carbon may be stored for a few decades. Thus, plantations end up carbon neutral at best having achieved no long-term benefits.

Unfortunately, the carbon accounting and reward systems in Australia encourage the use of plantation type forests after bush fires rather than assisting the natural but slower reforestation processes. Some of these decisions are influenced by the severity of the fires. This again emphasises the importance of doing everything we can to fight all wildfires as quickly and efficiently as possible.

What Happens If Forests Stop Absorbing Carbon? Ask Finland

Natural sinks of forests and peat were key to Finland’s ambitious target to be carbon neutral by 2035. But now, the land has started emitting more greenhouse gases than it stores. (https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/oct/15/finland-emissions-target-forests-peatlands-sinks-abs)

In a country of 5.6 million people with nearly 70% covered by forests and peatlands, many assumed the plan would not be a problem.

For decades, the country’s forests and peatlands had reliably removed more carbon from the atmosphere than they released. But from about 2010, the amount the land absorbed started to decline, slowly at first, then rapidly. By 2018, Finland’s land sink – the phrase scientists use to describe something that absorbs more carbon than it releases – had vanished.

Finland’s forests were mostly planted after WW2. In other words, they are mainly plantation forests. Commercial logging of forests – including rare primeval ecosystems formed since the last ice age – has increased from an already relentless pace, now making up the majority of emissions from Finland’s land sector.

Higher temperatures are causing the peat to break down and release CO2.

It has been suggested that by reducing the amount of logging and better management of their forests, the situation could be turned around. However, Finland’s Finance Ministry estimates that harvesting a third less would reduce GDP by 2.1%.

Finland is now forced to reduce its emissions by other means and won’t reach its Net Zero Target any time soon.

Are Australia’s Tropical Forests Becoming Net Carbon Sources?

An October 2025 paper published in Nature looking at Australian moist tropical forests used half a centuries’ data on above ground biomass as a measure of carbon sequestration. The above ground biomass was determined by measuring the girth and the height of every tree in each plot.

The study reported that a transition from carbon sink (0.62 ± 0.04 tonnes C /ha/ yr: 1971–2000) to carbon source (−0.93 ± 0.11 tonnes C /ha/ yr: 2010–2019) had occurred. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09497-8

Standing carbon stored in the trees dropped almost 30% to about 200 tonnes of carbon/ha yet these Australian forests continue to be among the most carbon-dense terrestrial ecosystems on the planet as well as harbouring a very high proportion of Australia’s remaining biodiversity.

The trees are only living half as long. Death rates have doubled. Degradation has been caused by cyclones and high winds, invasive species, higher temperatures and loss of soil moisture. Canopy leaves die in hot dry weather. There has also been a change in fire regimes. Loss of pollinating species such as the spectacled flying fox means that there are less seeds to regenerate the forests. Clearing and fragmentation of the forest in earlier years left the forest more vulnerable.

Importantly, in this particular study other vegetation was excluded as was carbon stored below ground in the soil and plant roots. However, luckily this forest is still a net sink when biomass underground is considered. Could that change?

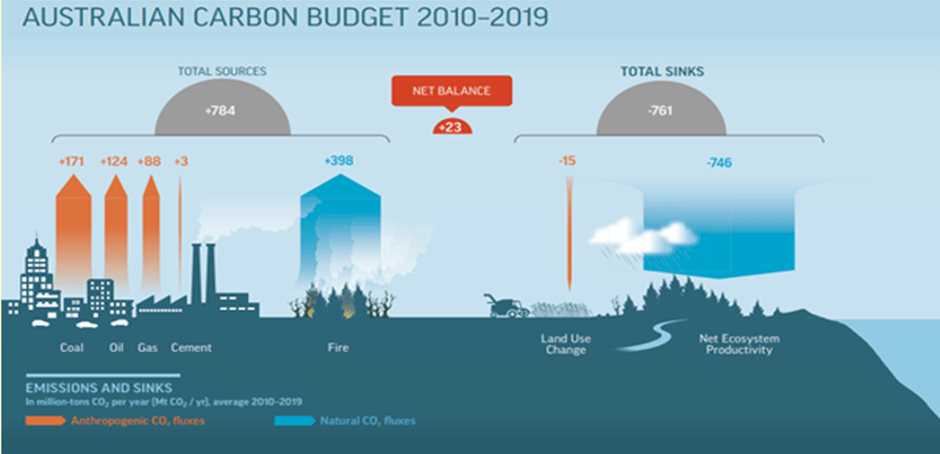

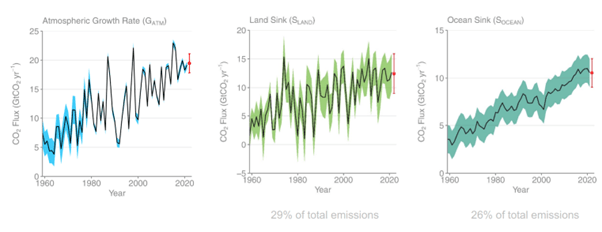

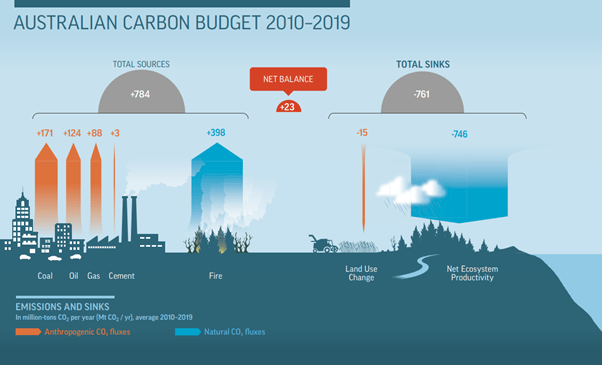

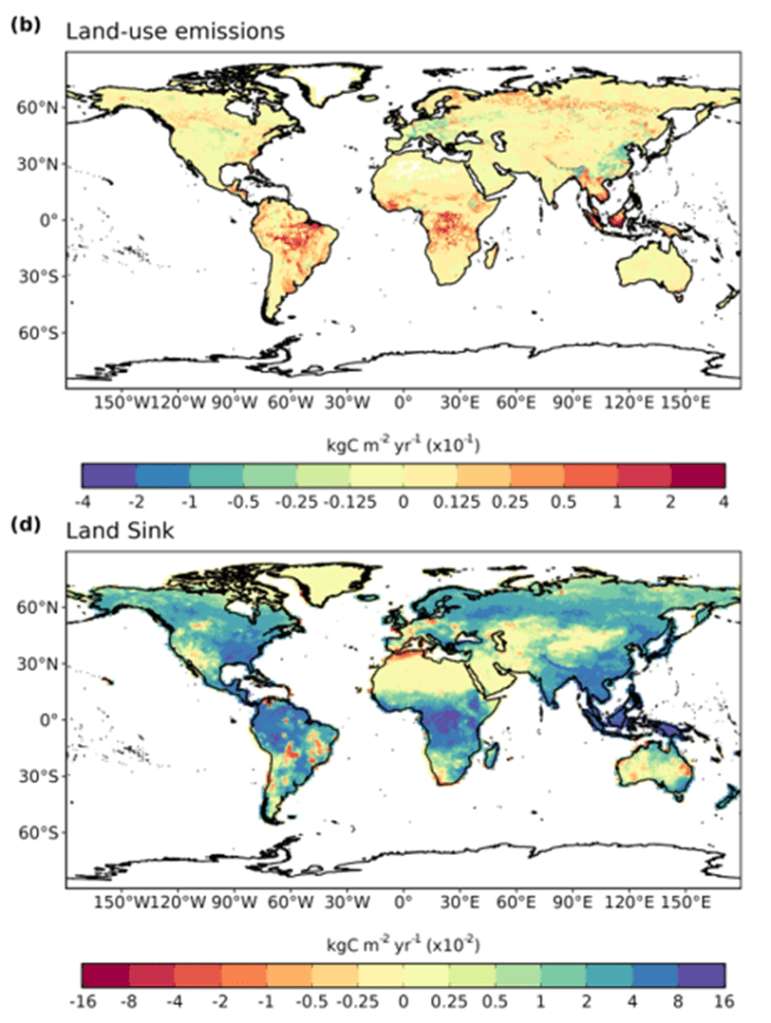

The World’s Land Sinks and Sources in 2024

Ref: Global Carbon Project Carbon Budget 2024 slides

Note that the land of southern Queensland, despite its remaining forest, is now a carbon source.

Many areas around the world are close to a tipping point.

The Amazon basin is showing many areas of stress, the most important natural forest areas of the world. The upper Amazon River and tributaries dried out for the first time in recent years.

A wrecked canoe lies in the dry bed of the Amazon River near San Augusto, Peru. IMAGE CREDIT: Plinio Pizango Hualinga/Rainforest Foundation US

How Much Degradation Can a Forest Take Before Becoming a Net Carbon Source?

An intact native forest will be a carbon sink.

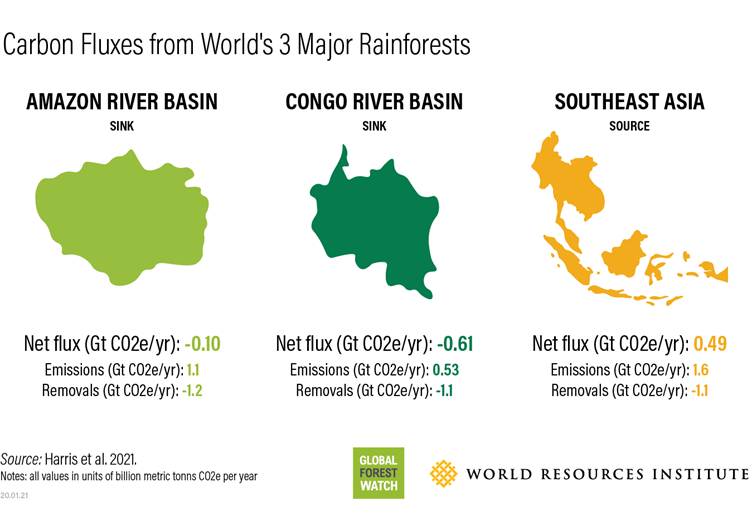

A disturbed forest may be a carbon sink or a carbon source depending on the nature and amount of disturbance. A forest can become a net carbon source long before being totally degraded. For example, in 2025 the Amazon Basin has now been degraded to the extent that it has become a net source rather than a net sink.

A badly degraded forest is a carbon source.

As temperatures climb, and land dries out, is there a tipping point? Of course there is!

It is not necessary to clear large areas within a forest to start it along the path to its tipping point. Studies in the Amazon basin have shown that clearing a little land in the middle of forest can dry out the soil for up to 3 km away. This has an effect on the water cycle and over time the damage gradually extends further and further into the forest.

Despite man’s disruption of some of our most important forests and increasing CO2 levels, nature has continued to remove 30 % of the carbon emissions we produce. Signs of strain are now showing. The oceans are not taking up quite the same amount that they were. The major tropical forests have sink areas but increasing source areas and the balance between sink and source is changing.

However, these forests still store hundreds of billions of tonnes of carbon.

Unfortunately, the current Net Zero protocols reward the creation of plantation forests at the expense of ecologically diverse established native forests. There is little reward for maintaining and looking after real forests. It is seen as beneficial to degrade forest to build short term mitigation structures, not considering the long term effects. We are neglecting the natural world by concentrating too much on economic drivers. Even less-intensively managed land has been made a poorer cousin.

Adapted from Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 1093–1114, 2023

What Will Happen to the World if Nature Stops Being a Net Carbon Sink?

We do need to cut emissions. It is not the basic concept of Net Zero that is the problem. It is how it is being implemented. We need a new way forward!

As temperatures climb, and land dries out, is there a tipping point? Of course there is!

Unfortunately, the current Net Zero protocols give the biggest rewards for the least effective behaviour.

How much more can we threaten our Australian forests before they crash and the eastern states become drier and drier and even hotter than necessary?

Please UN, COP and Australian Government find a way to reverse these trends. It is not too late!